What happens to optic neuritis as we age?

October 6, 2025 by admin Age-Related Changes in Optic Neuritis: A Comprehensive Medical Review

Age-Related Changes in Optic Neuritis: A Comprehensive Medical Review

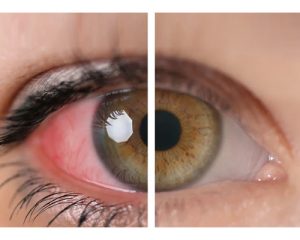

Optic neuritis (ON) is an inflammatory, demyelinating condition of the optic nerve that occurs acutely and is often associated with multiple sclerosis (MS) and other systemic diseases. It has been traditionally regarded as a disease of the younger population, yet new studies suggest that aging alters not only the clinical presentation and the underlying pathophysiology but also the diagnostic and therapeutic modalities applied in ON. The paper evaluates age-related physiological and pathological changes in ON and their ramifications on diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. The main goal is to inform the medical community—especially ophthalmologists, neurologists, and specialists in neuro-ophthalmology—about these significant age-related changes.

Epidemiology

Historically, optic neuritis was most commonly found in young adults, especially those aged 20 to 40 years. Nevertheless, the incidence of ON was not exclusive to that population. A bimodal incidence distribution of ON was suggested by the results of an epidemiological investigation, and the data from recent studies indicates that the elderly may present a new subset of the disorder.

Recent studies based on the general population found that although the incidence of optic neuritis in the whole population decreases with age, the inflammation might be more severe and the permanent loss of vision might be faster in older patients. Besides that, agerelated diseases such as heart problems or diabetes can make the situation worse by enhancing the inflammatory response or accelerating the process of demyelination. These findings highlight the need for different clinical approaches and treatment strategies for patients of different ages.

Pathophysiology and Physiological Changes with Aging

The pathophysiological mechanism of optic neuritis has long been understood as localized inflammation resulting in demyelination of the optic nerve. This process is mainly immune-mediated with the involvement of T-cells and B-cells leading to axonal damage and conduction block. In aging, the immune system and neural tissue undergo fundamental changes that affect their susceptibility to inflammation as well as their recovery.

Immunosenescence and Chronic Inflammation

Immunosenescence is the process by which the immune system’s ability to work properly declines as an individual gets older. Using a mild and chronic pro-inflammatory state, which is often called “inflammaging,” to describe the process, this phenomenon is manifested by a limited variety of naïve T and B cells, more memory cells, and so on. The changed immunological landscape in elderly patients with optic neuritis can lead, at least, to continued or even more intense inflammatory reactions, which may be one of the factors contributing to the increased incidence of axonal degeneration and poor visual prognosis among these patients.

The age-related chronic inflammatory environment in which older persons live can aggravate the ON induced acute inflammatory burst, thus increasing the extent of neural damage. The interaction between immunosenescence and acute inflammation may therefore result in a demyelination and neuronal death that is permanent, affecting the patient’s chances of recovery.

Demyelination and Remyelination in the Aging Optic Nerve

Demyelination is the process that degrades and removes the myelin sheath in optic neuritis and is the very root of the disease. Aging is the reason behind the decline of oligodendrocytes—the myelin-making cells in the central nervous system—regeneration. The aging process interferes with myelin production for the part because of the lower growth factor levels and a smaller number of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs). Therefore, older citizens suffering from optic neuritis may face a lesser chance of myelin integrity restoration after an inflammatory event.

Demyelination is the process that degrades and removes the myelin sheath in optic neuritis and is the very root of the disease. Aging is the reason behind the decline of oligodendrocytes—the myelin-making cells in the central nervous system—regeneration. The aging process interferes with myelin production for the part because of the lower growth factor levels and a smaller number of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs). Therefore, older citizens suffering from optic neuritis may face a lesser chance of myelin integrity restoration after an inflammatory event.

Also, the age-dependent extracellular matrix alterations, for instance, the increased accumulation of inhibitory molecules, could impede the movement and maturation of OPCs. At the same time, these alterations lead to anatomical recovery that is not fully optimal and thus could be the reason behind the longer recovery periods and incomplete visual restoration in older people. The altered immune landscape along with the remyelination deficit are barriers that make the treatment of aging populace difficult.

Clinical Presentation in the Aging Population

Classic optic neuritis is usually presented with the clinical triad of acute unilateral vision loss, discomfort on moving the eye, and abnormal color perception, however, the older patients treated with the same medications might show the clinical manifestations to be very different because of the physiological alterations mentioned above.

Atypical Symptomatology

It is typical for the older patients to show up with more subtle or uncommon symptoms. A study has shown that the elderly may feel less pain, or even have bilateral optic nerve involvement, which differs from the classic unilateral presentation that is usually seen in younger patients. Additionally, the older patients may have ocular comorbidities like cataract or age-related macular degeneration, and these ocular conditions may sometimes mask the clinical detection of inflammation in the optic nerve.

Visual Acuity and Field Defects

The acuity of vision in older patients with optic neuritis may suffer not only from the demyelination process but also from the degenerative age changes in the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and ganglion cells. The combined impact of the optic nerve’s aging and inflammatory damage can result in significant losses of both central and peripheral visual fields. In some situations, these changes may be indistinguishable from or overlap with other neurodegenerative diseases, thereby making the differential diagnosis more difficult.

For clinicians, it is imperative to carry out a complete ophthalmic examination with the inclusion of optical coherence tomography (OCT) and visual evoked potentials (VEPs) to be able to obtain a clear-cut differentiation between the age-related ocular pathology and the inflammation-induced damage that is characteristic of ON.

Diagnostic Implications and Considerations

The development of optic neuritis in elderly patients as a distinct disease has led to the need for a careful and complex approach to diagnosis. The standard diagnostic workup that includes clinical examination, imaging studies (MRI), and electrophysiological testing, needs to be modified carefully when it comes to older patients.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Age-Specific Findings

MRI is still considered the most important method for the investigation of suspected optic neuritis. In elderly patients, however, the presence of age-related changes such as microvascular ischemic lesions and white matter hyperintensities might be seen commonly, which can result in difficulty in interpreting MRI findings. Therefore, it is important for both radiologists and clinicians to be careful in linking white matter changes to demyelinating processes only.

Advanced imaging methods, like diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and high-resolution orbital MRI, potentially give more accurate information about the condition of the optic nerve fibers and can also distinguish between inflammatory demyelination and age-related structural changes.

Electrophysiological Studies: VEPs and OCT

Visual evoked potentials (VEPs) are a primary diagnostic method for validating demyelination. Nonetheless, age-related decay of conduction speed can affect VEP latencies independently, thus it is necessary to analyze these studies in the light of normative data which is age-adjusted for the patient.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) enables the measurement of retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness and retinal ganglion cell layer integrity. In geriatric patients, it is crucial to separate the normal age-related RNFL thinning from that caused by optic neuritis (ON) during the initial assessment. OCT performed repeatedly over a period can be a very useful way to observe the damage of the optic nerve over time and also to assess how effective the treatments are.

Treatment Considerations in the Aging Patient with Optic Neuritis

Primarily, the management of optic neuritis depends on the use of high-dose corticosteroids for acute inflammation, followed by a period of close follow-up by neurologists and ophthalmologists. However, age-related changes in the immune system and repair mechanisms require reconsideration of the dosage and duration of treatment.

Corticosteroid Therapy and its Adaptation for the Elderly

Corticosteroids are the primary treatment for acute ON. The high-dose steroid therapy has to be evaluated very carefully in elderly patients, as the potential for the development of corticosteroid-induced side effects like osteoporosis, hyperglycemia, and hypertension, which are very serious in an older population that is often affected by comorbidities, needs to be considered along with the benefits.

Several modifications to the standard corticosteroid regimen such as lower initial doses or shorter courses have been suggested in an attempt to lessen the risk of systemic side effects. The interdisciplinary collaboration between ophthalmologists, neurologists, and geriatricians enhances monitoring for complications.

Adjunct and Alternative Therapies

The altered remyelination capacities in older patients have raised the significance of exploring adjunct therapies to promote neural repair. The use of neuroprotective agents, which include sodium channel blockers, and the application of remyelination-making compounds, are still under adventitious research. Meanwhile, experimental treatments consisting of monoclonal antibodies aimed at modulating immune response or boosting OPC activity are being tested.

Given the age-related pathological alterations, these alternative therapies might provide the combined advantages of reducing inflammation and at the same time being supportive of remyelination. Still, conversion from clinical trials to everyday clinical practice is a long road ahead, with several agents that hold great promise still confined to preclinical or early clinical trial stages.

Managing Comorbidities and Their Impact on Treatment Outcomes

The probability of older patients having other systemic or ocular comorbidities like diabetes, hypertension, and glaucoma is higher. Such complications can affect the diagnosis as well as the course of optic neuritis. For example, diabetes can lead to microvascular insufficiency that will make the optic nerve ischemia worse, thus, visual deficits in ON might become more pronounced.

All these comorbidities should be tackled in one comprehensive treatment plan which will definitely include a multidisciplinary team working together to give the best care for the whole body. Not only does this method increase the management of optic neuritis as a whole but it also raises the recovery possibility besides minimizing the chance of future visual loss.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

The prognosis of optic neuritis in older individuals is not as promising as in younger patients primarily because of the additional impact of age-related neurodegenerative changes and a weakened ability to remyelinate. In contrast, older patients often lose more of their vision than younger ones, as the latter usually have fewer and more temporary deficits.

In the long run, research has shown that older patients with ON are at a higher risk of developing other neurodegenerative diseases like MS and NMOSD. However, not much is known about the natural history of ON in the aged population which stresses the necessity of continuous observational research to fine-tune prognostic models.

Regular OCT, VEPs, and MRI follow-ups are suggested for monitoring neurological and anatomical changes throughout the course of the disease. Clinicians are strongly recommended to observe visual functions with utmost care and in a very detailed manner so that they can apply the necessary treatments without delay when the disease comes back or progresses.

Future Directions and Research Considerations

The relationship between optic neuritis and aging still needs more exploration. The field of research is wide open for studies that will be conducted over longer periods, stratified by age, and that will be able to explain the exact pathways through which aging affects inflammation, demyelination, and neural repair. Future research may also be benefited by the use of multimodal imaging, molecular biomarkers, and genetic profiling in the context of the disease.

Research into the development of immunomodulatory agents that have specific indications during the elder patients’ age holds promise. The very fact that age progressively impairs the immune response makes it all the more interesting to develop drugs that can modulate this response without the risk of compromising the overall immune defense. Moreover, the possible effectiveness of lifestyle modifications and rehabilitation treatments in supporting the body’s natural repair processes may lead to the uncharted territory of the inlet for intensive ON management.

Interdisciplinary research projects that include neuro-ophthalmologists, immunologists, and geriatric specialists are pivotal for the creation of a personalized, age-based treatment plan. The foundation of normative data for OCT and VEPs in various age brackets will additionally delineate the diagnostic criteria and thus increase the sensitivity and specificity of these techniques in the aging population.

Conclusion

The incidence of optic neuritis in the elderly is a complex medical issue that calls for more in-depth knowledge of the general age-related changes in physiology and pathology. Immunosenescence, impaired remyelination, and the presence of co-morbidities all together lead to a more severe clinical course and a lower recovery capacity. This all-encompassing summarization underlines the necessity for a change in diagnostic methods, treatment schedules, and long-term monitoring regimes in the case of optic neuritis in older patients.

Understanding the relationship between aging and optic neuritis very well, is a must for ophthalmologists, neurologists, and neuro-ophthalmology specialists. Future studies should focus on the creation of new therapeutic measures that can meet the special difficulties posed by the aging process. The efforts to improve imaging for diagnosis and the unification of the procedures for the assessing of the elderly patients in terms of their electrophysiological status, will, in turn, make it possible for us to customize our interventions even more, which means better patient outcomes in the end.

To sum up, aging might modify the clinical picture of optic neuritis, but an integrated multidisciplinary approach could remarkably enhance the accuracy of diagnosis and effectiveness of treatment. It is imperative for medical professionals to keep abreast with the changes in the trends of the aging population and at the same time with the new evidence-based strategies in the management of optic neuritis, as such a shift in the composition of patients to older age groups continues.

The gradual and continuous progress of ON research with aging as one of the main factors is not only a challenge but also an opportunity to discover more precise and effective therapies. A deeper understanding of the situation may very well translate into a lessening of the long-term visual impairment commonly associated with the disorder and hence a better quality of life for elderly patients. Constant joint efforts among the specialists and age-targeted research will still be the main pillars of improving the management of optic neuritis in geriatrics.