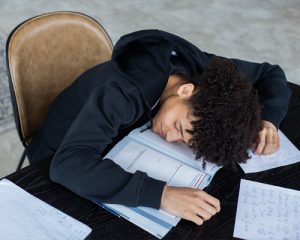

Sleep Deprivation

May 15, 2025 by adminSleep Deprivation – Its Introduction, Symptoms Present, Treatment, and Stages

Sleep deprivation is an ever-existing and complex clinical dilemma that manifests through physiological, psychological, and behavioral symptoms. It is a commonplace condition in contemporary society, and various acute and chronic health problems have been linked to it. This comprehensive article provides a detailed definition of sleep deprivation with respect to its pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnostic approaches, and management strategies, all illustrated by pertinent examples and case studies. This information is presented in advanced medical language with structuring conducive for health professionals and students to attain deeper comprehension of a multifactorial condition.

Sleep deprivation is an ever-existing and complex clinical dilemma that manifests through physiological, psychological, and behavioral symptoms. It is a commonplace condition in contemporary society, and various acute and chronic health problems have been linked to it. This comprehensive article provides a detailed definition of sleep deprivation with respect to its pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnostic approaches, and management strategies, all illustrated by pertinent examples and case studies. This information is presented in advanced medical language with structuring conducive for health professionals and students to attain deeper comprehension of a multifactorial condition.

Definition

Sleep deprivation is the state of an individual being deprived of a sufficient time or quality of sleep needed for normal physiological and cognitive restoration. It may be acute or chronic, with a variety of causes, including lifestyle, job-related issues, or medical and psychiatric disorders. Sleep deprivation is looked upon clinically if the total sleep hours fall short of what is considered normal according to age, usually less than 7 hours for most adults, or if the quality of sleep is so compromised that it interferes with normal restorative processes.

Disturbances in sleep are not conceived merely as an individual’s subjective perception of denial but are in fact accompanied by objective neurocognitive, autonomic, and metabolic alterations. For medical students, it should be kept in mind that the term “sleep debt” implies the accumulation of total sleep loss over a certain period that predisposes a patient to various health-related problems.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of sleep deprivation is a multi-system approach to explain the problem. On the one hand, the homeostatic drive to sleep is the primary regulating force of sleep. When awake for longer periods, adenosine gets produced. This substance induces sleepiness, hence initiating the sleep process. On the contrary, the circadian rhythm is generated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, which syncs physiological functions with the 24-hour day-night cycle.

In sleep deprivation, there is a huge disruption of these processes, altering the neurochemical pathways either for GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) or orexin/hypocretin, which is crucial for sleep regulation. This disruption is responsible for altered patterns of cortisol secretion, sleep loss in slow-wave sleep (deep sleep), and disturbed REM (rapid eye movement) sleep, subsequently culminating in cognitive impairment and mood impairment.

On the cellular level, sleep deprivation impairs synaptic plasticity that is required for memory consolidation and learning. A longer duration of waking has been correlated with the accumulation of metabolic by-products such as beta-amyloid, which may relate to neurodegenerative disorders. Cytokine levels, such as IL-6 or TNF-α, are increased with sleep deprivation and may contribute to endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular risk.

Case-based studies in vivo have documented that circumstantial shift workers and medical residents, who commonly experience circadian disruption, also see an increase in perceived sleepiness and, conversely, a real decrease in executive function and reaction times. Impairment of decision-making and psychomotor performance beyond the mere feeling of sleepiness is a critical clinical significance of sleep deprivation.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical Manifestations

The manifestations of the clinical aspect of sleep deprivation are numerous and involve multiple systems, with broad categorization into neurocognitive, cardiovascular, metabolic, immunological, and psychological categories.

Neurocognitive and Behavioral Impairments

One of the hallmark features of sleep deprivation is impaired cognitive performance. The affected individuals show decreased alertness and reaction times and lesser working memory and so on. These impairments are more particular with those requiring sustained attention in the line of work, such as health professionals and pilots. For example, sleep deprivation lowered the level of clinical judgment and increased the chances of medical errors in a case study involving an intern in a tertiary care hospital.

In addition, mood disturbances are likely to emerge, including irritability, anxiety, and depression. Together with dysregulation in neurotransmitter systems, especially those involved in serotonin and dopamine signaling, disrupt the feelings of the affected subjects. From a behavioral point of view, there is also impaired motivation and social interaction.

Cardiovascular and Metabolic Dysfunctions

By cardiovascular implication, sleep deprivation is brought about by heightened sympathetic nervous activity and drifting of parasympathetic tone. This imbalance in autonomic will then become primary in raising up blood pressure and heart rate and giving arrhythmogenic potential. Parallelly with the findings of longitudinal studies, chronic lack of sleep is linked to higher risk of developing high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, and stroke.

A disruption of normal sleep adversely affects glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. According to an RCT, even short-term sleep restriction causes significantly impaired glucose tolerance, therefore, increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Changes in the regulation of some hormones such as ghrelin and leptin favor weight gain and obesity.

Immunological Alterations

Sleep helps modulate the immune system. Lack of sleep increases pro-inflammatory cytokines potentially impairing immunological defenses. From a clinical viewpoint, it has been observed that patients suffering from chronic sleep deprivation develop infections more easily and take more time to recover from illnesses.

During influenza epidemics, for example, healthcare workers with irregular sleep schedules were observed to suffer from viral infections more often than their well-rested colleagues; this example serves to underline the importance of interplay between the sleep and the immune function.

Psychological and Psychiatric Sequelae

Additional to cognitive impairments, long-term sleep deprivation can engender or aggravate psychiatric disorders. There is abundant evidence correlating chronic loss of sleep with an increase of major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, and, in the harshest scenarios, psychotic symptoms. The bidirectional relationship between sleep and mood disorders suggests that sleep deprivation may be both a cause and a consequence of psychiatric pathology.

One illustrative case involved a middle-aged patient with a history of bipolar disorder who experienced a manic episode following an extended period of sleep restriction due to occupational stress. The case throws a spotlight on the risk of insufficient sleep exacerbating pre-existing psychiatric conditions.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of sleep deprivation requires a thorough workup consisting of a complete sleep history together with physical examination and sometimes objective sleep studies. Subjective methods are employed in conjunction with quantifiable analyses to assess the existence and possible effects of sleep deprivation.

Sleep History and Clinical Interview

The initial step is a detailed sleep history encompassing sleep patterns together with duration and subjective quality. Clinicians usually rely on the use of validated questionnaires such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) or the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) to obtain quantitative measures of sleep disturbance and daytime sleep

The crucial step of assessment starts with a detailed sleep history comprising a study of sleep patterns, duration, and quality. Clinicians usually use validated scales to rate sleep disturbances and daytime sleepiness, such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) or the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). It becomes pertinent to discuss lifestyle, work demands, and other stresses that can contribute to sleep deprivation.

Objective Sleep Studies

In patients with significant daytime impairment or when there is suspicion of other sleep disorders, objective evaluations such as polysomnography (PSG) become necessary. PSG provides a multi-parameter assessment including electroencephalography (EEG), electrooculography (EOG), electromyography (EMG), and respiratory evaluation, facilitating a detailed analysis of sleep architecture and stages.

Actigraphy, another valuable tool, involves the use of a wearable device to monitor sleep-wake patterns over an extended period, typically in an ambulatory setting. Actigraphy data can help corroborate findings from sleep diaries and clinical interviews, particularly in cases of suspected circadian rhythm disorders.

In such an interview, a detailed inquiry about associated medical illnesses, psychiatric disorders, and use of substances (including caffeine, alcohol, or illicit substances) is relevant to rules-out aggravating factors. In many occasions, the sleep history may give clues about features of a primary sleep disorder-an insomnia or an apnoea-may coexist with secondary sleep deprivation.

Laboratory and Ancillary Testing

There is no given biomarker for sleep deprivation; nevertheless, for some patients, laboratory investigations might be needed to include or exclude metabolic, endocrine, or neurological disorders that could mimic or exacerbate sleep loss. For example, thyroid function, cortisol, and blood glucose levels are commonly checked in patients with complained unexplained fatigue and sleep disturbances.

Management

Management of sleep deprivation is very complex with a consideration of both non-pharmacological and pharmacological remedies. Restoration of adequate sleep duration and quality to alleviate the neurocognitive, cardiovascular, metabolic, and psychiatric sequelae is the foremost goal. Furthermore, an individualized plan addressing etiology and contributing factors should be formulated.

Non-pharmacologic Interventions

Sleep Hygiene Education

Sleep hygiene is a primary treatment concept. This means a patient should be taught the practices that increase good sleep, such as keeping a regular sleep schedule, maintaining a proper environment for sleep (e.g., noise reduction, controlled light exposure, comfortable bedns), and avoiding stimulants such as caffeine and nicotine before going to bed. Evidence suggests that even minimal behavior changes may produce substantial improvements in sleep quality.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I)

CBT-I is a structured intervention that is tried and tested and treats the cognitive and behavioral elements of insomnia or sleep deprivation. It encourages stimulus control, sleep restriction therapy, and cognitive restructuring to break down the cycle of dysfunctional sleep behaviors and maladaptive thoughts that reinforce them. It has been demonstrated that CBT-I brings about permanent improvements and is used as the primary treatment in many instances of chronic insomnia with associated sleep deprivation.

Chronotherapy and Light Exposure

Chronotherapy and appropriately timed bright light exposure can benefit patients with a disruption of their circadian rhythm. Chronotherapy consists essentially of gradually manipulating sleep timing to watch realignment of the circadian clock, while bright light therapy in the morning helps in suppression of melatonin release in the day and also in bringing on wakefulness. These are best suited to use in shift work and delayed sleep phase syndrome.

Behavioral Modifications and Stress Management

Stress and anxiety can certainly be both causes and effects of sleep deprivation. Using interventions like mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), relaxation techniques, and regular physical exercise can reduce stress and help facilitate better sleep patterns. In clinical practice, a combination of lifestyle changes with psychological assistance helps maximize the effectiveness of treatment.

Pharmacologic Interventions

A pharmacologic approach may sometimes be justified along with non-pharmacologic measures, especially when non-medical interventions do not adequately work for the patient. Considerations of side effects, dependence, and tolerance should therefore always guide and influence decisions to pursue medication treatment.

Sedative-Hypnotics

Benzodiazepines and zolpidem- and eszopiclone-type benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BZRAs) are popular prescriptions given for short-term acute sleep deprivation. These agents initiate and maintain sleep by enhancing the inhibitory activity of GABA at the central nervous system (CNS). However, they need to be used only for limited durations because of the danger of dependence and rebound insomnia.

Melatonin and Melatonin Receptor Agonists

The pineal hormone melatonin serves to regulate the sleep-wake cycle. In instances where circadian rhythms are disrupted, melatonin supplementation or the administration of melatonin receptor agonists, such as ramelteon, can be an option. They align the circadian clock with the external environment and are preferred for their safety profile.

Wake-Promoting Agents

There are instances when wake-promoting agents such as modafinil or armodafinil are prescribed, especially in the setting of excessive daytime sleepiness due to chronic sleep deprivation. With these agents, one does not treat the underlying cause of the sleep deprivation; rather, they enhance alertness and cognitive function, leading to greater safety in occupations with a high level of responsibility. In a study involving a population of long-haul truck drivers, the medically supervised administration of modafinil was shown to decrease roadside accident risk significantly by reducing the effect of sleep loss on psychomotor performance.

Adjunctive Therapies

Other pharmacologic agents considered include low-dose doses of antidepressants, e.g., trazodone, and some antipsychotics used off-label for sleep, in those presenting with comorbid mood or anxiety disorders. These agents would have the added advantage of treating both affective syndrome and sleep disturbances but shall always be approached as per patient profile and monitored closely for any side effects.

Monitoring and Follow-Up

Continual monitoring and follow-up are at the core of managing sleep deprivation. Patients are advised to keep a diary recording sleep parameters such as sleep quality, sleep duration, and any intervention undertaken. Should there be regular assessments, clinicians would be better placed to gauge the effectiveness of the various measures, identify any emerging side effects, and make appropriate recommendations.

The Multidisciplinary Approaches and Case Reviews constitute the lifeblood of academic and clinical medicine, especially in the setting of patients with refractory symptoms or with multiple comorbid states. Follow-up exams must also screen for the development of related medical conditions such as depression, cardiovascular disease, or metabolic syndrome to promote a more holistic approach toward patient care.

Case Studies and Real-Life Examples

The following case studies highlight the multifactorial nature of sleep deprivation, emphasizing the importance of early intervention:

Case Study 1: The Shift Worker

The patient was a 42-year-old man who worked in a manufacturing plant. He presented with complaints of chronic fatigue, poor concentration, and intermittent headaches. Very conscientious measures were taken toward sleep hygiene, yet the patient’s shift work interfered with his circadian alignment. Actigraphy revealed an abnormal pattern of sleep-wake cycles with numerous awakenings during nights. After a detailed evaluation, the patient entered a structured chronotherapy program with adjunctive light exposure therapy. Over three months, the patient experienced remarkable improvements in sleep and functioning during the day, thus validating behavioral treatments in circadian rhythm disorders.

Case Study 2: The Medical Resident

A 29-year-old resident in a tertiary care teaching hospital was exposed to progressive cognitive impairment, irritability, and lapses in clinical judgment during prolonged duty hours. Polysomnography revealed an almost complete reduction in REM and slow-wave sleep stages. The resident was advised about sleep deprivation-related consequences and was enrolled in CBT-I. For pharmacologic management, a melatonin receptor agonist was administered in low doses to induce a normal circadian rhythm. Later tests showed improvement in sleep architecture and cognitive function, as well as a concomitant decrease in reported stress. The case brings out the very important issue that some institutional changes are necessary for healthy health practices at work, especially in clinical environments that are high in stress.

Case Study 3: The Patient with Comorbid Psychiatric Illness

A 35-year-old lady with a past history of bipolar disorder had insomnia for sleep onset and worsening mood instability. Manic episodes ensued in which sleep deprivation had played a strong precipitating role. A treatment plan was established, including mood stabilization and CBT-I, with gradual tapering of benzodiazepines. Over 6 months, the patient showed great stabilization of mood alongside significant gains in sleep quality. This case further strengthens the relationship between sleep physiology and psychiatric well-being, thereby emphasizing the need for collaborative approaches in management.

Implications for Future Research and Clinical Practice

As the emerging data continue to unravel the intricate interrelationships between sleep deprivation, neurodegeneration, and systemic pathologies, the advancement of modern neuroimaging facilitates the detection of particular brain changes of structural and functional connotations associated with chronic sleep loss. Hence, the growing imperative has led to the consideration of very-long-term neurological outcomes. Genetic considerations through polymorphisms in disposition to sleep disorders remain an unfolding area of current interest. In time, this will evolve into the discovery and application of novel biomarkers and therapeutics to advance the clinical management of sleep deprivation.

At the clinical level, there is the need for an integrated multidisciplinary approach comprising behavioral modifications, pharmacological management, and patient education to optimize outcomes. It is important for health care institutions to make sleep health a high priority while targeting those groups who are at a high risk, including health care professionals, shift workers, and persons with pre-existing psychiatric or metabolic disorders.

Conclusion

Lack of sleep is a crucial problem in public health and carries quite serious consequences for health and productivity. The pathophysiology of this condition is manifold; disturbances affect neurochemical signaling, circadian rhythms, and immune modulation, among others, resulting in a myriad of clinical presentations-from cognitive impairment to metabolic dysfunction and even mood disturbances. Diagnosing sleep deprivation requires some subjective impressions and objective investigations, while it should be treated through an integrative multimodal approach comprising both behavioral and pharmaceutical approaches.

The article aims at giving an overview of the sleep deprivation topic contextualized within clinical data and intertwined with case studies to highlight the varying challenges encountered by patients. For the practicing physician and the medical student, learning about sleep deprivation should extend past solely knowing its apparent symptoms toward understanding the underlying pathophysiologic processes, knowing how to test for these, and identifying the most suitable and individualized treatment plans.

In light of emerging descriptive and mechanistic aspects of normal and abnormal sleep, clinicians must keep in mind and constantly evaluate patients for the presence of sleep deprivation, counteracting its deep shadow cast on individual health outcomes and overall quality of life.